September 23, 2025

Oddbox and the complex truth about plastic

.jpg)

September 23, 2025

.jpg)

Earlier in the summer, I had my first viral post on LinkedIn! I shared about my experience with Oddbox, and how I felt that the volume of plastic inside the box had increased and quality decreased, to the point that I’d decided to cancel my subscription and switch to an alternative.

That post clearly hit a nerve with the LinkedIn community: nearly half a million impressions and hundreds of comments and reactions. If I could bottle the formula I would! But that's not today's topic...

As well as a few new followers it also drew the attention of the team at Oddbox. They reached out and I was lucky to have a wonderful conversation with their co-founder and their head of sourcing about their business model and some of the challenges I had observed as a customer.

Their openness and willingness to engage was awesome, they set the record straight on a few things, and we threw around some potential solutions. Overall it was an enlightening and enjoyable chat.

The reason, I think, why the post resonated so loudly with the community is really a lesson in marketing and communications. It represented the confluence of three competing factors:

In this article, I’d like to break down each of these areas, before looking at what it can mean for fresh food retailers like Oddbox and beyond.

The Oddbox model is somewhat unique in the world of food retail.

Their mission is to reduce food waste by providing a secondary market for growers to distribute surplus or wonky vegetables directly to customers (Oddbox). It’s a laudable mission: food loss and waste accounts for around 8-10% of annual greenhouse gas emissions globally (UNFCC).

Oddbox explained to me that they don’t have their own direct growers and don’t own any farms. Instead, they work closely with a wide range of producers to identify cases where they forecast a surplus that can’t be met under existing contracts. And then they seek to match this up with their subscriber base, rescuing and selling on as much as they can.

We spoke about how there can be a common perception that ‘rescue’ means stuff that was sitting around in barns, unsold and nearing the end of its life. However in practice the supply chain is quite different.

Of course it takes many weeks to grow vegetables, and producers generally know ahead of time what crops will look like. Perhaps it was a particularly abundant growing season, and they have more than can be delivered to existing buyers. Or perhaps a sudden unexpected turn of the weather damaged a crop cosmetically, making it unlikely to be taken by a supermarket.

The Oddbox team pride themselves on delivering freshly picked vegetables and take quality very seriously. Because their team works closely with growers to identify ahead of time how much surplus they can take based on their customer orders, the growers will pick to order for them when crops are ready. This means their veg is just as fresh as from the supermarket - perhaps more so. Just less predictable.

It’s a great model, and in my view they just don’t communicate it powerfully enough. Unfortunately that can leave consumers to jump to their own conclusions, and all it takes is one dodgy item on the turn to reinforce a set of assumptions.

Similarly, when it comes to primary packaging, because Oddbox don't own the relationship with growers, they can’t always control what things are packaged in. Sometimes items may be rescued after they are packaged, and it makes little sense to remove the plastic before delivering to customers.

Other times there is a conscious choice to package things before transport to prolong their life or protect their quality on their way to the customer. When reducing food waste is the mission focus, tackling damage and loss in transit is an important aspect of that.

Yet there’s a huge gulf between consumer sentiment (plastic = bad), especially for more conscientious customers, and the realities of food packaging and logistics (something we’ll explore in more depth shortly).

One of the challenges with that is setting and meeting customer expectations. If marketing comms show lots of pictures of crisp loose veg, then this is what customers will expect.

When practicality means some things need to be packaged for freshness or protection, that can be jarring when it's not what customers expect or understand.

We spoke about how those expectations could be managed through UX design, for example communicating items that are commonly packaged in plastic (and why) as part of weekly box contents or swap features, or providing choice for consumers to opt out of some commonly packaged items.

The Oddbox team also floated the idea of a plastic free box option, which is a great idea for placing the consumer back in control. Of course it comes with trade-offs - perhaps it will mean never getting salad leaves or rainbow chard (no great loss in my view!) - but as long as those are clearly communicated, then giving customers choice feels like a strong option.

The team said they are actively exploring that as a potential option in future, so I’m excited to see if it gets implemented.

The relationship between primary packaging (plastic in particular) and food waste is a complex and emotive one.

On the one hand, plastic has many important qualities that can help prevent spoilage and prolong shelf-life, two of the leading contributors to food waste at transit, retail and consumer level. Emissions due to food loss and waste are huge, up to 5bn tonnes CO2e per year globally. That’s comparable to the aviation or fashion industry.

On the other hand it's hard to argue that the production, use and disposal of plastic doesn’t present its own set of environmental challenges: from the emissions and environmental damage of extraction, refining, manufacture and disposal, to the complexities of recycling.

For example only 10% of plastic packaging that could be recycled actually is (Wrap). Of that, most can only be recycled several times before they break down, and the process often involves injection of virgin feedstock and can leach toxic chemicals and microplastics back into the environment.

A number of studies have explored the interplay between those two impacts, and the results are far from clear cut.

All that research and debate, in my view, can be summed up by three key challenges:

Around 2011, when the UK was exploring introducing a levy to reduce the use of plastic carrier bags (an overwhelmingly effective initiative by the way; The Guardian), several government reports were commissioned looking at the relative environmental impact of different carrier bag materials.

A report by the Northern Ireland Assembly (source) argued that when the impact of production is considered, plastic bags, especially if reused, produce less greenhouse gas emissions than paper or textile bags.

And an unpublished report by the Environment Agency (referenced in the briefing note although never actually released; Independent) also found that paper carrier bags require four times the energy to produce than plastic, and have less reuse potential, leading them to conclude that paper carrier bags are worse for the environment.

The findings were picked up at the time by several major news outlets, and continue to be referenced directly and indirectly, including in a 2019 BBC article, and even on Oddbox’s website.

However, while the relative impact between paper and plastic bags in this case may well be accurate, there are a number of nuanced issues with the Northern Ireland Assembly study, that are worth breaking down:

First off, the paper does not contain any original scientific research. As an internal briefing note it draws exclusively on internet research. Most of the sources cited are no longer available, and included many third-party and commercial websites, such as:

Next, the research relates to tertiary packaging (specifically carrier bags), and the potential for reuse is a big factor that influences the environmental impact. The impact of single use primary food packaging, which has a much higher volume and much lower recycling and reuse capacity, is not explored (although it is in several other studies).

The research takes a narrow view on impact, mostly focusing on a comparison of equivalent greenhouse gas emissions, and omits a full lifecycle analysis (LCA). When a 2014 paper by NRCM sought to correct many of common assumptions and conducted a more in depth LCA, they found the impact of paper and plastic to be much closer than previously reported (NCRM). Similarly a 2024 study found that while plastic overall has a lower footprint it still has a negative impact on several planetary boundaries and has a higher impact than paper on ozone depletion, and flooding (ScienceDirect).

And finally, the research fails to account properly for the actual retail environment and consumer behaviour in their assessment. For example, many small businesses (that fall out of the scope of the levy) still use HDPE carrier bags, and most consumers do not reuse them again. Similarly, the study calculated that a cloth bag would need to be reused 171 times to be equivalent to the emissions of a single plastic bag. In practice cotton tote bags are often used for many years, and will last much, much, longer than a plastic or paper reusable bag.

The reality is the interplay between retail and consumer, food waste, shelf-life and packaging is complex and difficult to measure.

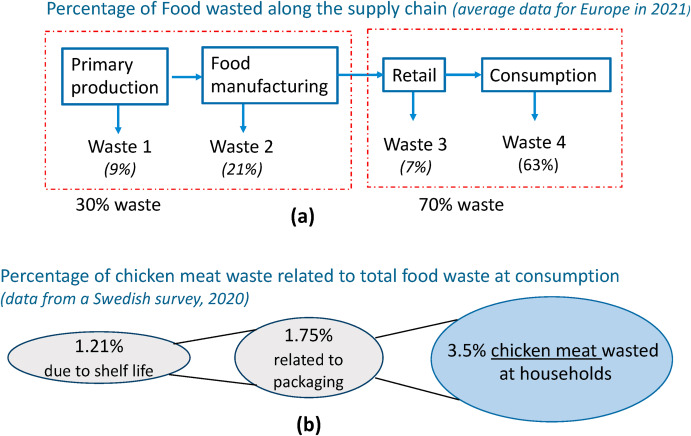

One 2024 study from a team at University of Lleida in Spain found that comparative models to assess the effect of packaging and shelf-life on waste were not well defined. While they concluded that some packaging was better than no packaging when it came to managing waste (they looked specifically at chicken meat), there was still no consistent accepted way to measure impact:

Currently, there is no scientific consensus on using a specific model to estimate food waste at a given shelf life of a packaged product. (ScienceDirect).

Similarly another study from 2024 (ScienceDirect) highlighted that the impact of microplastics pollution on the environment and human health was generally not well understood and tended to be neglected in existing LCAs on plastic packaging. This ommission, they claim, can lead to paradoxical and misleading results from plastic LCAs which often overstate the relative benefits of plastics:

Plastic LCAs may have limitations and can be prone to misuse. Many LCAs of plastics fail to include the EoL phase, which results in plastics being favoured as a material choice, despite the fact that they may continue to degrade and release harmful substances into the environment.

And an earlier study from 2023, focusing on different cold transport systems, found that packaging weight and distance were also significant factors when it comes to environmental impact, not just material choice (ScienceDirect):

The results suggest that conclusions regarding lower environmental impact cannot be exclusively based on the choice of insulation material. The weight of the packaging and the transportation distance also exert a significant influence on the overall environmental performance of the systems.

Where that early 2011 briefing note sought to provide definitive answers to inform policy, what many of the more recent studies suggest is that the problem of food packaging and waste is highly nuanced and context dependent, and that holistic LCAs are needed.

Interestingly, the Spanish team presented data to show that 70% of food waste is at consumer level, with the two largest contributing factors being items exceeding their use date while still in packaging, or spoiling once opened. This suggests that while packaging may be important for tackling loss and waste in transit and retail, a large unexplored area is around consumer behaviour too (more on that shortly):

In our world of relative plenty, we have become accustomed to buying more than we need, and lax about using or preserving all of what we have. Different packaging systems won’t necessarily fix this - some may help to reduce it, but the real challenge is one how retail innovation can help nudge the consumer towards better behaviours.

In all the debate and discussion, I’ve observed an interesting philosophical assumption about primary packaging, and it goes something like this:

If you want the convenience of fresh vegetables, anywhere, anytime, then plastic is a necessary evil (or wonder material, depending who you ask) that you’re just going to have to accept.

Food waste causes more greenhouse gas emissions than plastic, and impacts more planetary boundaries.

Therefore it’s ok to use plastic to fight food waste.

There’s a baked in assumption there that it’s either-or. Either go plastic free and waste food, or accept plastic and cut waste.

But it’s a narrow assumption, and as we know the world doesn’t operate on binaries.

Here’s some alternative angles:

The choice between convenience or plastic-free is not always one consumers are exposed to, but is perhaps one it’s time to address.

With the majority of food waste down at the consumer level, it raises the question ofhow we can influence that behaviour towards better outcomes, and where responsibility lies in doing so.

I am a firm believer that we can't place responsibility solely at the foot of the consumer, whether that is better educating themselves or going out of their way to change. Aside from the fact that human psychology says the majority won't bother, the average consumer is only really responding to what is available in the marketplace.

But what we can do is establish a set of principles to help guide retail experiences, industry policies, and consumer choice, with the goal of tackling food and packaging waste at the same time.

Mindful that the real world is one of constant compromise between good intentions and practical reality, I think it looks something like this:

With the majority of food waste due to spoilage at home, by minimising surplus at home, we can minimise the amount that goes off before its used.

If you can’t, then buy to last

Buy with long shelf-life in mind: UHT, dried, tinned, preserved, and make a plan to store what you can't use now for later.

The further things have to come, and the longer they spend in transit, has two impacts: it increases the chance it spoils on the way, and increases the reliance on packaging (especially plastics) to ensure it reaches you fresh. By shopping local we minimise the food miles and reduce both these impacts.

If you can’t, then buy resilient and seasonal

Some things don’t travel well without a lot of packaging and some things come from far away when out of their local growing season - do we really need then, and can we wait?

The best kind of packaging is no packaging. Where choice exists, and where it won’t lead to avoidable waste (see above) then buying loose and using reusable containers can help to minimse the impact of packaging.

If you can’t, then buy optimal

Aim to minimise packaging to produce ratio through buying in bulk (mindful of the above) or buying appropriate to the season thus reducing packaging miles involved.

In our modern society where we’ve grown increasingly detached from the means of production, retailers like Oddbox are incredibly well placed to help reconnect consumers with where their food comes from and encourage more sustainable consumption.

While primary packaging, and in particular plastic, is an important solution in tackling food waste, it's a downstream solution and one that doesn't really tackle the underlying problem. I would love to see a brand like Oddbox exploring how to influence growers to switch to more sustainable (and by that I mean more long-term feasible as well as lower impact) solutions that help move us towards a future that is both low-waste and plastic free.

They are, for example, sitting on an incredible data opportunity around real consumer preference. It would be fascinating to offer opt-outs on products commonly packaged in plastic and measure what the data says about what customers actually choose, using this to exert leverage on producers and packaging manufacturers.

And while having food delivered to your door is certainly peak 21st century convenience, the veg box is such an amazingly simple solution to tackle the modern problem of overconsumption and waste. For those without easy access to farm shops and local producers, or who are too busy juggling jobs and families to pop out every time they need a few things, it’s a route to fresh, locally sourced produce, in sensible week on week volumes.

But if there’s one takeout from this debate, it’s how retailers like Oddbox can help consumers to understand a little more about the complexities of how produce gets from farms to their forks, so they can be a little more conscious about the choices they make and the price they pay for convenience.

I’d like to thank the team at Oddbox for engaging so readily with this topic and reaching out in a way that not many brands would have done. I’m looking forward to see how they continue to evolve their offering.